“We take a guided tour of Rod Millen’s personal collection”

Whatever else makes it famous, the Coromandel Peninsula has never been known for motorsport. But, thanks to Rod Millen — one of the most iconic figures in New Zealand motorsport — that is beginning to change. The reason is his Leadfoot Festival, which is one hell of a driveway party held annually in February at his Hahei ranch. For the rest of the year, the ranch is much like Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory, as the large wooden gates are rarely opened to the public. Housed on the property is a car collection that serves as a chronicle of Millen’s career, from running rallies in New Zealand when he was scraping together pennies and sacrificing everything to realize his motorsport dreams to running rallies in Europe, Asia, and America, alongside involvement in other forms of racing from hill climbs to stadium trucks, off-road, Indy, and the 24 Hours of Daytona. Rod spent the majority of his life living in America, where he built up a very successful business as well as adding his initials to many motorsport record books. But, once he retired, he and his wife Shelley settled in Hahei and brought their huge car collection with them, and this month Rod offered his time to walk us through it all.

The oversized ranch gates swung open as the man who needs no introduction to anyone with even the most fleeting interest in New Zealand motorsport history pulled up alongside. Photographer Richard Opie and myself did feel like we were Charlie and his granddad waiting at Willie Wonka’s gate (Richard can be the grandad), but, instead of a chocolate factory, we were about to enter the holy grail of garages, located smack-bang at the centre of the ranch. As we followed Millen to the barn along his driveway-cum-race-track, the countless in-car videos we’ve watched began to kick in, and it all became familiar: that’s the start line, that’s where the Rat Trap ended up in the drink, there’s where ‘Mad Mike’ Whiddett tagged the brick wall going over the bridge, and then the long black marks from Shane Allen and the Rattla Falcon lead us right to a set of barn doors.

The first barn we found ourselves in is actually the workshop where the famed Pikes Peak Celica and Rod’s Mazda RX-3 rally tribute car were awaiting some maintenance. Over the back was the farm shed housing a few yet-to-be restored project cars that I had no idea even existed, and then we were off to the main barn, where most of his competition machines (the ones that survived) are housed. Apart from the yet-to-be-restored machines, everything else is ready to run, and, as in the past, a handful of them will be driven in anger at next year’s Leadfoot festival.

When you chat to Rod, he instantly comes across as a down-to-earth Kiwi petrolhead. You nearly forget this man built an empire while also engineering a ridiculous number of race machines, each more innovative than the last. His company, MillenWorks, built military and concept machines and developed industry-leading technology. Rod told me, “When I sold the company, I had 70 really good mechanical and electrical engineers and designers and a full machine shop and fabrication shop with all the CNCs and that. We put a lot of effort into design. We had some really good guys working on unmanned vehicles and hybrid-electric stuff for the military. Our first hybrid electric was in ’93 that we had running around, with lead-acid batteries. So, the battery technology was not there, but we had all the rest of the system there, and we knew that the battery systems would eventually come around, as they did. In different [motorsport] programmes we got involved with, we could grab different talents for periods of time to work on something unique and special.”

But enough of the small talk, we were here to look at his cars. Let the geek fest begin!

The Celica

To most of you reading this, the Celica will be one of the more familiar machines in Rod’s stable. Sure, he did plenty of great stuff earlier in his career, but the Celica really cemented the Millen name in history. To go out and smash the Pikes Peak’s overall record by a massive 39 seconds was a once-in-a-lifetime achievement, and, though I’m not a betting man, I would drop $1K on a bet that this feat will never be repeated.

To achieve it took a serious programme, and there is no denying it also took a huge budget with some serious partners on board, including Toyota. Rod put together a team of his best, as he explained: “The bit I enjoyed more than anything was putting together the group of people and sitting down with a somewhat clean sheet of paper and coming up with what we could design and build. We had been going to Pikes Peak since ’81, not every year, but most. We had built a variety of different 4WD cars in the early independent suspension, NA [naturally aspirated] and turbo cars, so we had a really good group of people to work together with.”

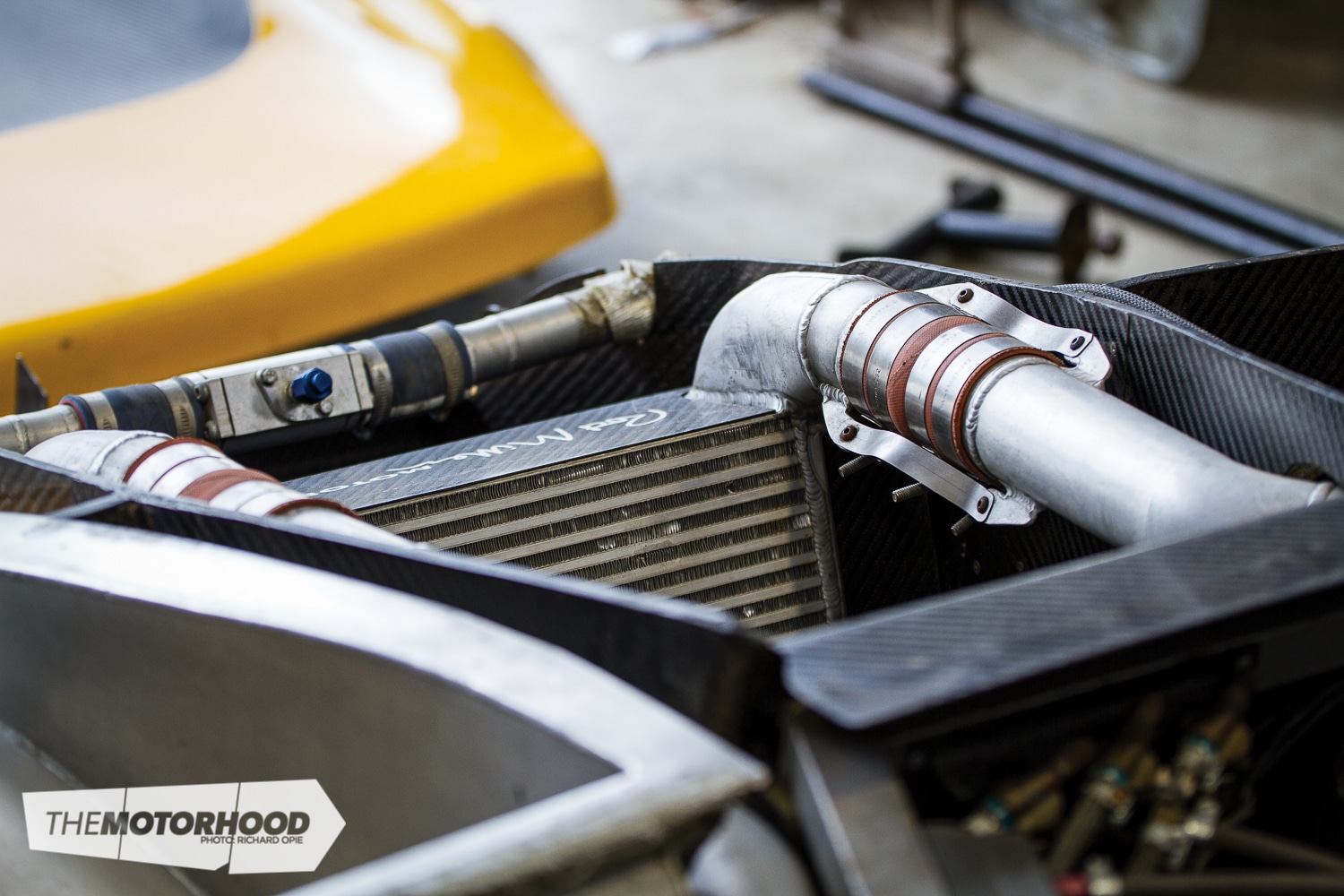

When building a car for the Pikes’ Unlimited Class, there really was only one rule: the car had to resemble a manufacturer’s model. In the years beforehand, the team had built big-power 4WD machines, but, this time around, there was a new tool in the arsenal, something that would be instrumental in the Celica’s success: aerodynamics. “Lee Dykstra — a well-known guy in IndyCar circles — and professor Joseph Cates out of the University of San Diego, who was also well known, designed the aero. Yes, we wanted to keep the Celica-shape silhouette, which was important to Toyota, but they took that shape and morphed it into what they needed to get the right aerodynamics. It was all modelled on a Cray supercomputer; these days it would be much easier [you can download and run more powerful programs on your laptop], but, 22 years ago, it required a lot of computing power to look at what it would do.”

Being forced to stick to the exterior shape meant that it was all about utilizing the underside to get downforce. Two large venturis run from just behind the firewall, and exit the rear bumper. Removing this air as efficiently as possible is the job of that large rear wing, and its primary task is to create as much negative airflow behind the car as possible. But, being 4WD, it’s not all about rear downforce — frontal downforce is just as important. This is also handled by large venturis, which take air from big front dams, through coolers, to exit via the rear of the front wheels.

After all the shapes had been modelled by the supercomputer, Rod’s in-house team then produced the carbon panels, but time constraints meant that, in the first year, some of the actual plugs were run complete with excess bog, something Rod laughs about now.

Before they ran at Pikes in ’94, the team spent time at 1220 metres, testing and refining the car’s limits in the El Mirage desert to prove the aerodynamic shapes, in what was, effectively, a real-world wind tunnel, as Rod recalled: “We then went to the El Mirage dry lakes in the Mojave Desert. We would do 100mph [161kph] passes in each direction and measure the effects of downforce using instrumentation on the suspension. Throughout the few days, we would do lots of little changes on the car to see what each adjustment we would make to the car in terms of total downforce or front and rear, and so on.” The Celica performed, creating a massive 907kg (2000 pounds) of downforce at only 161kph. And, from there on up, it’s not a linear curve — it’s quite aggressive — and, by top speed (around 275kph), the car is creating a massive 1360kg. The Celica weighs 862kg, which means that, at only 161kph, it could easily drive on the ceiling.

The next stage of development saw the team rent out Pikes Peak, something Rod tells us you could do for three hours each morning before the public toll road opened. “When we started testing at Pikes Peak, I knew what we wanted in terms of roll stiffness front and rear, being 4WD, and for handling and stuff ike that at low speed, but I had no idea what it would mean at high speed. It took us quite a while to get the high-speed balance right, which became the aerodynamic balance. One of the biggest things I had to change was my driving style, as, the way the front venturis are shaped, I can’t have any more than about 15 degrees of slip angle, or otherwise it doesn’t load air properly into the venturis and it doesn’t get the turn-in. Modern race cars won’t even allow that much slip, but they knew that we needed some slip, certainly around the tight corners. So, as long as, in my terms, I kept the car straight, it was very, very good.”

But the testing wasn’t just for Rod’s team; it was also used by BF Goodrich, which brought along five different compounds to trial. Back then, the surface at Pikes was rough granite. It was a tyre killer and running only 10psi of pressure didn’t help. BF took away all the data and put together a compound especially to provide maximum grip and last the 19.98km and 156 corners. Even with a specially designed compound, it was still up to Rod to minimize tyre spin, something that was not easy with a wild (early 1990s-tech) laggy turbo and 635-odd kilowatts. “Up near the top, they are getting pretty shagged,” he said. “With this sort of power on gravel roads, you spin the tyres real quick. Just learning how to manage that — there is 18 times you go back into first gear through the hairpins, so getting off the hairpins, which, in most cases, is a steep uphill, you just have to be very careful on the throttle. Short shifting and getting it back in top gear as effectively as you can, it’s easy to drive the thing wild and quite sideways; it’s quite fun actually, but it’s not fast.”

The engine was the one area in the entire build, bar the tyres, that Rod’s team didn’t need to worry about. Rod explained that the backing of Toyota, which made its very successful four-cylinder turbo engines available to the team, was a huge step up. These packages had run in the IMSA series with Dan Gurney and obliterated the likes of the V12 Jaguars and Porsches. They had also dominated in things like the 24 Hours of Daytona. The motor had a specially cast block running upwards of 895kW in qualifying trim — TRD had developed a monster. Rod mentioned that he recently chatted to the engineer in charge of the engines and was told that only one in five blocks cast ever made it into a car.

Would you believe that that record-setting engine is still in the Celica to this very day? That was something which certainly surprised us, when you think just how highly strung it is. Said Rod, “When they ran these engines, they never pulled them out if they were good. They had a history; if they were reliable they were really reliable, and if they were going to fail they would do so very early on. So, they went on the basis of just putting new motors into those cars, and if it was good it was left in there.”

In the Celica, the engine was pushing 45psi and 633kW, with Bosch engine management the size of Michael Jordan’s shoebox and a large-frame Garrett turbo. During testing, TRD sent a team of technicians to Pikes so they could fine-tune the set-up to cope with the altitude and still make the numbers. Over the course of the run, the car would lose around 150kW due to the thinner air.

Well, we all know the rest. Rod went on to stamp his name into the history books with a run of 1min 4.060s, and then, in 1996, he managed to shave a further .006s off the record. Thirteen years later, the Celica still couldn’t be touched. Even when the team developed the Tacoma two years later — a car that Rod explains as being light years ahead of the Celica — it was not able to touch the record, although it did take back-to-back Unlimited Class victories. It wasn’t until the course was 100-per-cent tarmac in 2007 that the record was broken, by Monster Tajima.

It’s a little old-school tech now, but the Celica’s still got it. It’s a constant top-10 place-getter at the Goodwood Festival of Speed when it’s up there, and, here on Rod’s drive, it also remains king. And, despite what you might think, it’s not like Rod practises in it every week. The only time it’s out is during the Leadfoot Festival, and, even then, he doesn’t want to be too hard on the old girl, as he is trying to make it last a long time. But with the 100 years of Pikes coming up next year, there is talk of the car heading back, though Rod is not sure whether he can get the old gang back together for one last hurrah, and the Toyota would need work that might affect its mana as an unaltered piece of history.

Rod comes across as someone who does nothing by halves, and he is never just there to fill a place on a grid, so an appearance would not just be a leisurely drive up the mountain. Even in his graceful old age, you can see the fire in Rod’s eyes — the same fire that I bet was there when he started running hill climbs on Auckland’s North Shore in the 1950s. If he does decide to go, you can be sure that he will be there to run some competitive numbers.

This concludes part one, but look out on Sunday, March 27 for part two, which features Rod’s Championship RX-7, the Works RWD RX-7, the back-flip truck, the Stadium truck, the Tundra, and much, much more!

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

This article was originally published in NZ Performance Car Issue No. 230. You can pick up a print copy or a digital copy of the magazine below: