There are many scenarios in which a compression test will come in handy, especially if you’d like to know more about the condition of a motor but can’t strip it down. Perhaps, for example, you’re looking into buying a second-hand motor or are just interested in the condition of your current, running motor. A compression test is one of the most telling indicators of engine condition, indicative of how well the combustion chamber is holding pressure. A good and consistent reading across all cylinders implies healthy piston rings and valve sealing, whereas poor or inconsistent readings may be indicative of either top end or bottom end problems. It’s also important to note that ‘cranking compression’ is not the same as the ‘compression ratio’. ‘Cranking compression’ measures the pressure generated in a combustion chamber when cranking to indicate how well, or otherwise, that cylinder is sealing. The ‘compression ratio’, on the other hand, is just a formula to determine the combustion chamber’s volume at bottom dead centre (BDC) as a ratio of its volume at top dead centre (TDC).

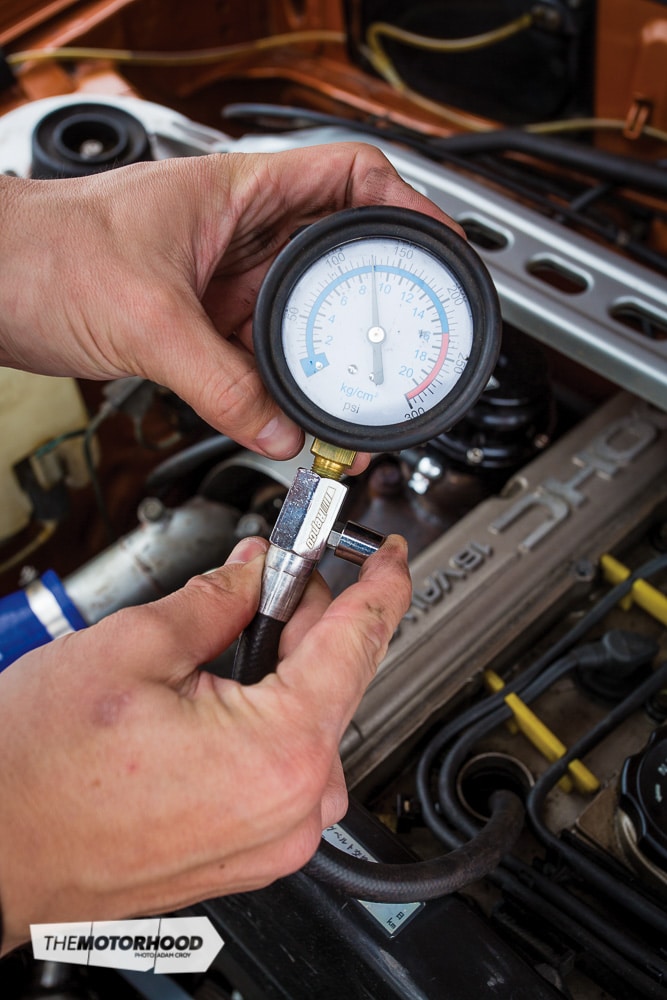

Most compression-tester kits recommend testing an engine’s cranking compression when it’s reached operating temperature, although testing an engine cold may not be an unwise idea — see the breakout box to the right. Here, we tested this more for the owner’s knowledge than anything else. In a Mitsubishi 4G63T, a cranking compression reading of between around 130–170psi is considered acceptable, but more important than the numbers themselves is consistency — a 20-per-cent difference or less across the board is considered OK.

Cold testing

A cold engine’s pistons and rings won’t have experienced thermal expansion, so a cold compression test could be more truthful about the bottom end’s real condition. Compression test each cylinder cold, and identify any that gives an inconsistently low reading. Squirt a small quantity of oil into the cylinder through the spark-plug hole then retest. The oil will provide a supplementary seal to the rings between the piston and the bore, and a compression reading that is around 10 per cent or higher than the cold test indicates wear in either the piston rings or the cylinder bore.

How it works

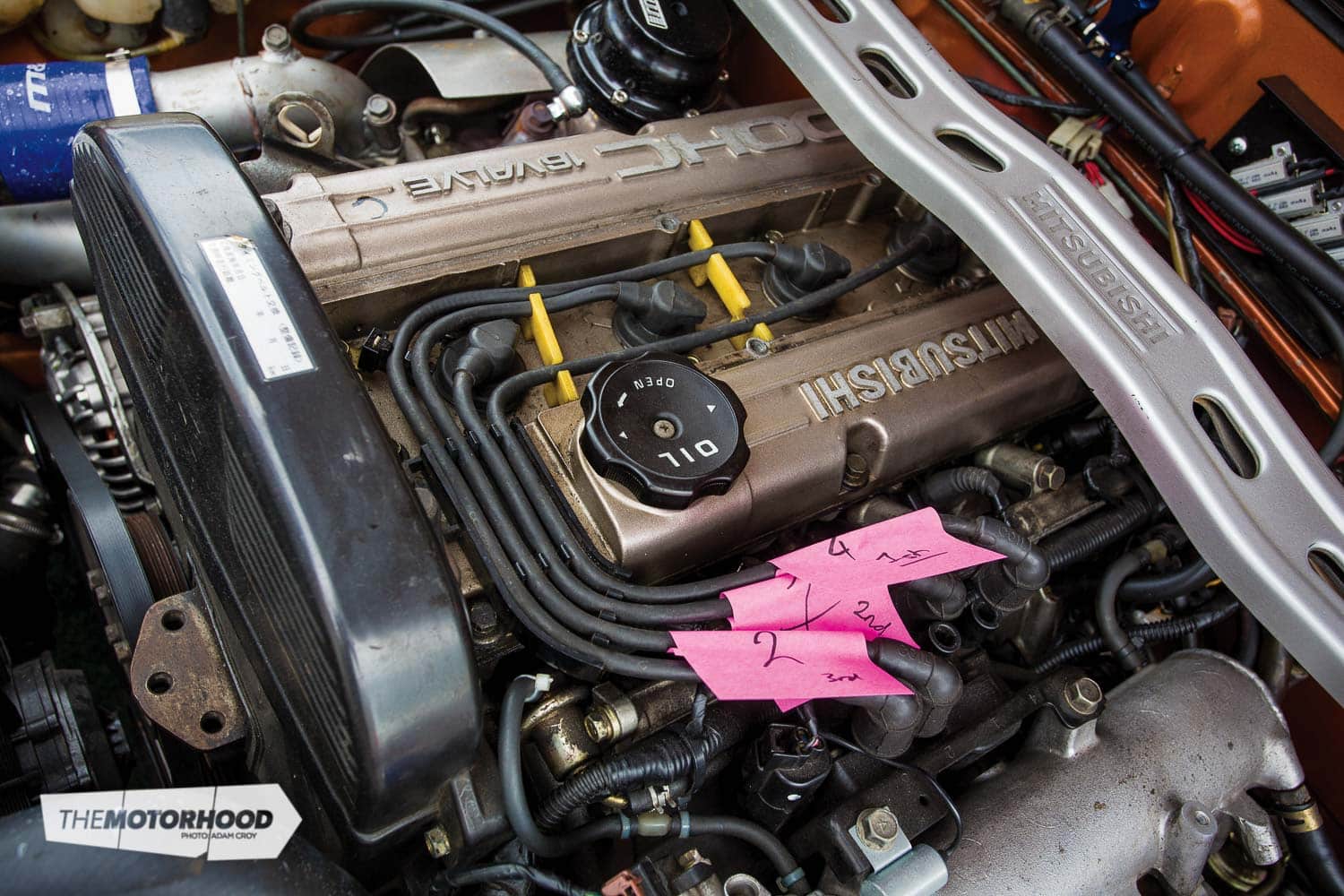

If you want to perform the compression test at operating temperature [we performed this test cold], the first thing to do is to run the engine up to that temperature. Once that has been done, disconnect the coil — or coil packs in this case — to ensure the engine won’t fire when cranking. As this Mitsubishi runs coil packs, the leads were unplugged at the coils and marked for their original positions.

Remove the cylinder one spark plug and match the spark-plug thread to the compression-tester thread if you’re unsure what fitting you need — most compression testers come with a range of threaded fittings to ensure they’ll work in a range of motors.

Thread the compression tester into the spark-plug hole by hand. You don’t need to go overboard with the tightness; just ensure it’s threaded in sufficiently so that pressure can build behind it.

Double-check that the ignition system is disconnected so that it won’t fire. Ensure that the throttle is wide open, then crank the motor for at least five compression cycles. You’ll hear a puff of compressed air with each cycle.

Note the pressure reading (in psi) for that cylinder, and write it down. You’ll want to compare it with the rest to determine the variance between each cylinder’s cranking compression.

Before removing the compression tester, depress the bleed valve to vent the compressed air to the atmosphere safely.

You can now thread the tester out of the spark-plug hole and move on to the next cylinder.

This article originally appeared in NZ Performance Car Issue No. 230. You can pick up a print copy or a digital copy of the magazine below: