data-animation-override>

“When Donn Anderson first tested an RX-7 some 35 years ago, he was so impressed he bought one”

From day one, the original Mazda RX-7 was a sales sensation. Cars changing hands for premium above-list prices were nothing unusual in New Zealand in the late ’70s, yet almost unknown in North America — until the arrival of Mazda’s unique rotary-engined RX-7.

Here was a handsome sports car with European-like styling, a remarkable silky-smooth motor, and superb build quality, for less than the price of a Porsche 924 or Datsun 280Z. It went on sale in the US for under $7000 and Mazda could not cope with demand, despite importing 4000 a month. Near-new examples in the US fetched $3000 over the recommended retail, and much more in New Zealand.

While the car had real appeal in markets like Europe, Australia and New Zealand, it was the US that cemented the success of the model.

Of the 474,565 first-generation RX-7s made between 1978 and 1985, no fewer than 377,878 went to the States.

The local market

Before the large-scale arrival of Japanese used cars, there were never enough RX-7s to satisfy our market. First examples arriving here in 1979 retailed at $18,000 but realized more than $25,000 on the used market, even after a year or two. By 1981 the New Zealand new price had climbed to $26,000, $33,425 in 1983 and $40,000 in 1984. When the last ones landed in early 1986 they had skyrocketed to more than $48,000. They were followed by the second generation, newly bodied P747 cars — the price having risen to $71,500 by the time they arrived on our shores.

With the influx of ex-overseas used versions, original first-generation models became much more affordable, and always seemingly destined to become a future classic. And surely, that time is now.

Rotary power

Replacing the RX-3, the first RX-7 carried several designations, including X605, SA22C and FB, with early planning in place by 1974. The project was lucky to get off the ground, since the sometimes fickle and thirsty rotary had been widely blamed for Mazda woes in America.

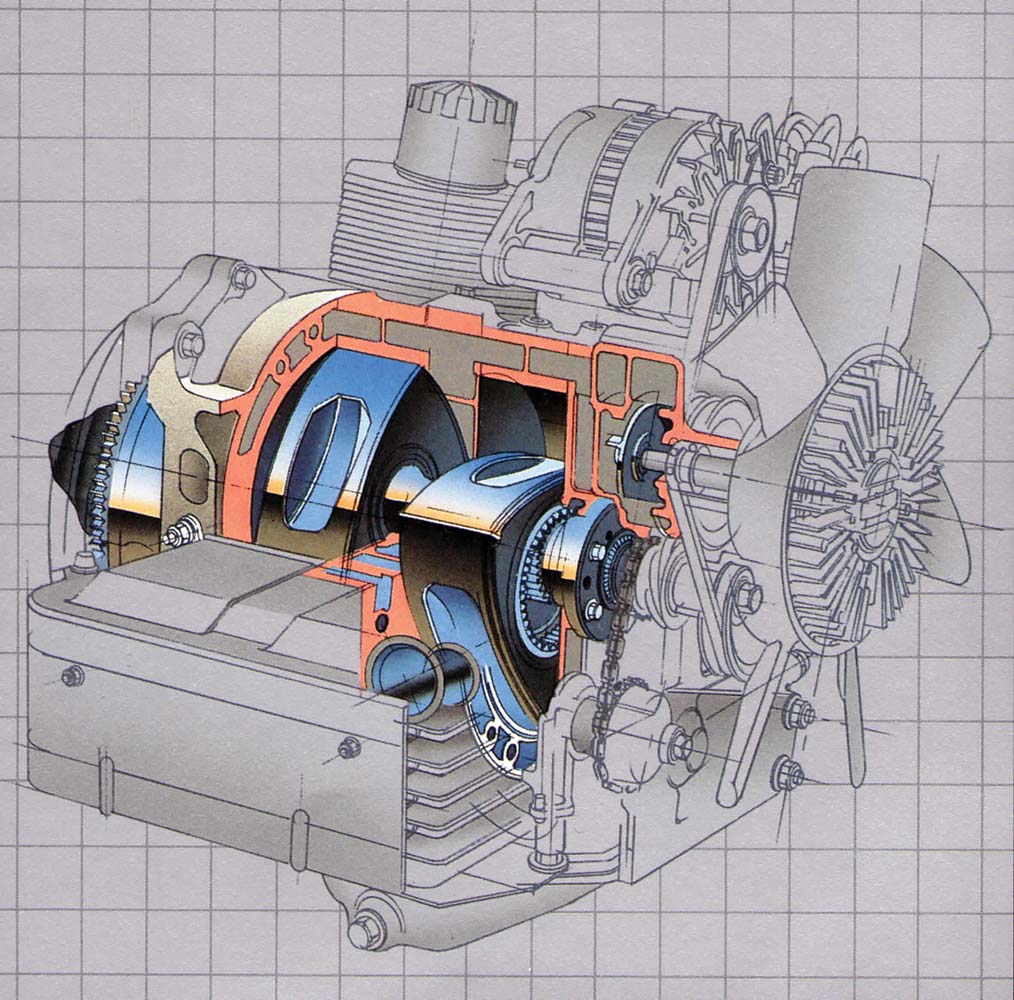

In the early ’70s half of all Mazdas were powered by rotary engines, but the first oil crisis devastated sales, forcing a rethink. NSU had announced rotary engine production in November 1959, and Toyo Kogyo (Mazda) signed a contract in July 1961 to develop and make its own version of the revolutionary power unit, with the two-door Cosmo Sport twin-rotor launching in 1967. Yet this ambitious swing to rotary power almost pushed Mazda into bankruptcy.

The RX-7 marked a turning point for the rotary, a time of acceptance. As the snappy new sports car swung into production, Mazda could lean on the experience of 16 years of rotary engine development, and the manufacture of more than a million of this radical power plant.

Enter Takaharu ‘Koby’ Kobayakawa, a talented engineer who was vice president of Mazda research and development in North America. He had joined the company in 1963 as a member of the original rotary engine development team.

In 1980, when I met Koby at Mazda’s Hiroshima headquarters, he was manager of international public relations, and would go on to become the RX-7 programme manager for the third-generation model in the latter stages of the ’80s. Unlike ‘gen one’, this was, indeed, a supercar with its 198kW, two-rotor engine with twin turbos and a stonking 253kph (157mph) top speed. It was difficult not to be impressed and warmed by Koby, whose career with Mazda included overseeing the brand’s historic win with the rotary-powered 787B in the 1991 Le Mans 24 hour race.

A real enthusiast

Koby was clearly a real enthusiast (his father owned an MG K3 Magnette), and a man who believed that a good sports car should always create an intimate relationship between car and driver. He reckoned the rotary engine was intrinsic to any RX-7, since it distinguished Mazda from all others. In addition to being the top-selling rotary car of all time, the RX-7 became the world’s best-selling sports car, only to lose the title to yet another Mazda — the MX-5 — 10 years later.

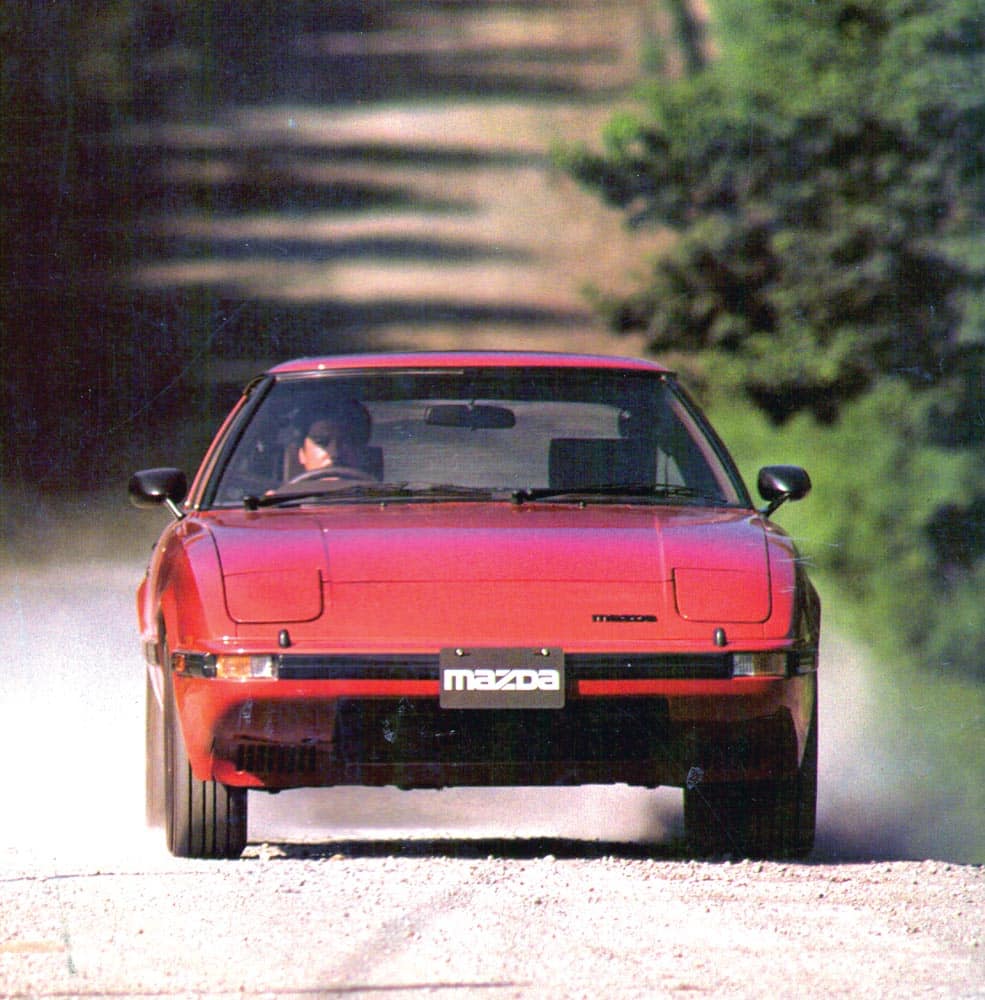

Rewind to the ’70s and applaud the simplicity and balance of the original RX-7. From inception, the car’s designers insisted on retractable headlights and a single-piece wraparound rear window as part of the smooth, functional body, but because of cost and weight considerations the production car came with a three-piece window. While most Japanese cars of the era suffered from garish over-adornment, the RX-7 emerged with a shape that is just as appealing today as it was 36 years ago.

The compact rotary engine weighed only 142kg and allowed the Mazda to have a low bonnet line, with a drag coefficient of 0.36 and a 195kph top speed. Minimal styling changes on the 1981 Series 2, which ran from 1981 to 1983, included a new urethane-covered front bumper/air dam that further lowered the drag to 0.34, equivalent to a gain of 3.7kW. Disc brakes replaced rear drums, and a thermally more efficient engine produced 85kW (114bhp), up from 77kW (103bhp) in the original RX-7. Improvements to the face-lifted RX-7 rotary included larger, secondary intake ports, a revised position for two of the four spark plugs, modified combustion chambers machined into the rotors, better sealing between the rotors, and a new exhaust system with less back pressure.

The second-generation FC P747 (1986-1988) boasted a completely new shape, while the third-generation twin-turbo FD that ran until 2002 was a more sophisticated beast, although it measured no more than the 4285mm of the original Series 1. While the car’s evolution saw improvements and greater refinement, none of the subsequent-model RX-7s could emulate the phenomenal eight-year sales success of the original.

The Kiwi rotary connection

Rotary-engined cars were not new to New Zealanders. The first rotary-powered car to be built in Australasia rolled out of the Motor Holdings Otahuhu plant in October 1972, and the RX-2 Capella and RX-3 both went into local assembly. In 1975, 1976 and 1977, Aucklander Rod Millen won New Zealand’s national rally championship no less than three times with an RX-3, before moving to Los Angeles to become a full-time rally driver. He campaigned an RX-7, and in 1981 clinched the North American rally championship in the Mazda, with seven wins, two seconds and two thirds in what was a remarkable result. The following year Millen won his class in an RX-7, and was sixth overall in New Zealand’s international rally.

He went a step further in 1983 with his ingenious bespoke four-wheel-drive RX-7, taking the prototype to victory in only its second rally in North America. With the compact nature of the rotary engine and ideal weight distribution, the Millen Mazda was immediately competitive, clocking 217kph on a radar during the rally while still picking up speed. In place of the standard 12A rotary, Rod fitted a 13B peripheral-port intake and exhaust two-rotary engine, with carburation provided by a 51mm Weber. Keeping it simple and using as many standard Mazda parts as possible, Millen campaigned the 4WD RX-7 for three seasons.

Externally the rally car looked little different from standard RX-7s, but it ran 14-inch-diameter Panasport wheels in place of the standard 13-inch alloys. Weismann’s transmission research and development company made the power take-off unit that adapted to the rear end of the transmission. The Mazda’s differential was also modified, and front-wheel-drive suspension and drivetrain parts from the Mazda 626 were cleanly mated to the front of the RX-7. This common use of standard parts by Rod impressed Mazda.

The live rear axle with trailing links and Watts linkage was sometimes considered the weakest feature in the production RX-7 (and was replaced on the 1986 second-generation car with a fully independent set-up), but Millen strengthened the axle, added Tokico gas dampers and a limited-slip differential. The standard unassisted, low geared, recirculating-ball steering was never a design high point, so it was not surprising Rod swapped this for a rack-and-pinion system. When the 4WD conversion was completed, only 45kg had been added to the weight of the car, and, with around 225kW (302bhp) under the bonnet, the Mazda was an impressive performer. However, Kobayakawa dismissed the idea of a 4WD RX-7 ever going into production, because he thought it had no place in a traditional sports car.

On test

When I first tested an RX-7 on local roads in 1979, the rotary engine’s flexibility and responsiveness impressed, as did its remarkable smoothness, although there was a tendency for backfiring on a trailing throttle, and a lack of conventional engine braking. Bottom-end power was limited even though the engine was remarkably vibration free, with an absence of flat spots in the power delivery. Low-speed torque would be improved on facelifted models, yet still peaked higher up the rev range and was clearly not brilliant. The car was inclined to hunt on over-run, and could be jerky in city and urban running due to the flywheel effect of the engine.

Back in 1979, the popping on a trailing throttle during the warm-up period was due to the high level of lead in our petrol, and was nothing to worry about, according to Mazda. But that rotary engine was indeed a revelation the way it spun like a top, with the warning buzzer sounding each time the power unit exceeded 6700rpm.

Even today anyone impressed by fine engineering cannot help but admire the under-bonnet scene. The engine compartment is immaculately laid out, with easy access to distributor, carburettor and spark plugs. There’s even a small motor to set the throttle at the correct opening when the car is fired up. The engine is located well back in the compartment behind the front wheels, contributing to the near ideal weight distribution.

Oil consumption could be high, and the motor was sensitive to spark plugs which sometimes oiled up. And, of course, the often savagely high fuel consumption was the result of the combustion chamber sweeping past the spark plugs, making it difficult to ensure complete combustion before the expanding gases departed the exhaust port. During my rural test run, the RX-7 averaged 10.2 litres/100km (27.7mpg) but work the car hard and drivers could be looking at 15.6l/100km (18.1mpg) and worse.

However, there was always something special about this car, and when a low mileage, mint condition example became available in 1980 I leaped at the opportunity to own what was a driver’s delight. It proved totally reliable and fuss-free during my tenure, and I was sorry to eventually sell it.

Japanese classic

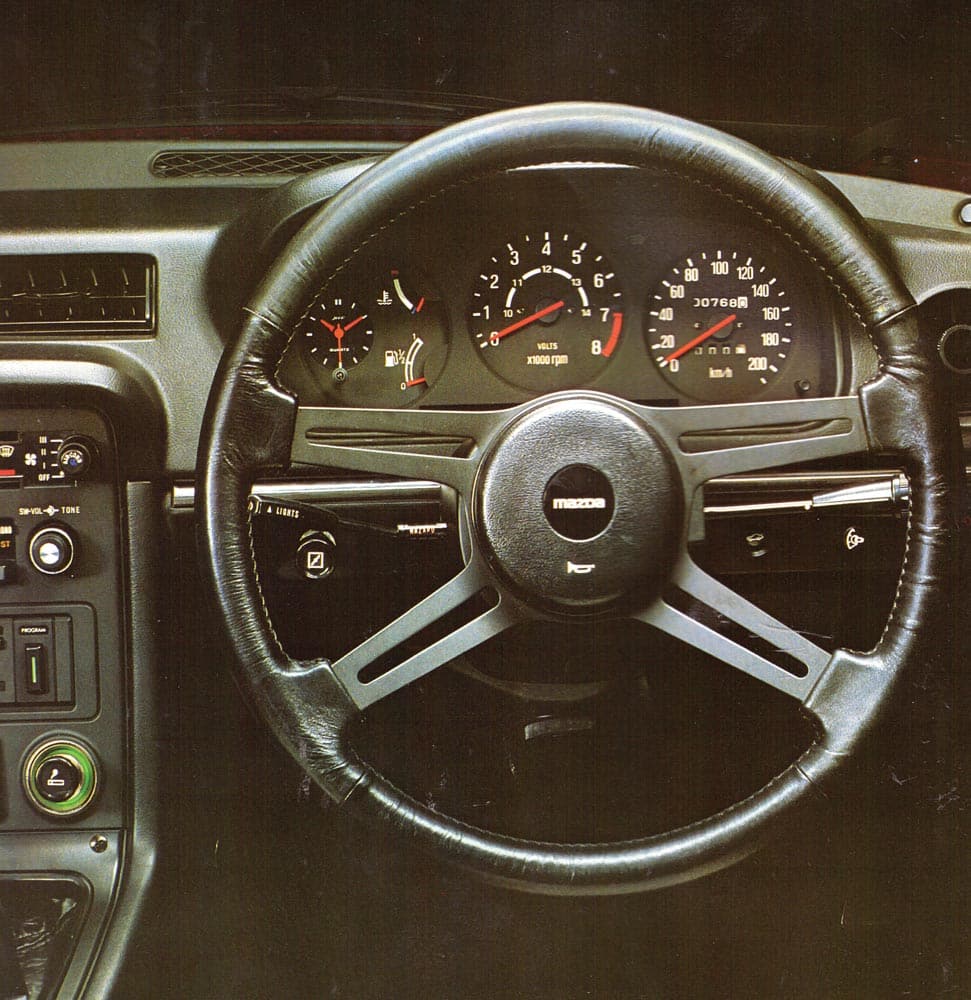

Perhaps the most desirable of the first-generation RX-7s are the cleaner-looking Series 2 and 3 models, with their revised bumpers, smoother rear end with tidier tail lights and number plate positioning, better brakes and upgraded interiors. The gear lever was also repositioned closer to the driver and weight of the steering eased, but power assistance was still unavailable. A new sound system fed through four speakers instead of two, the windows were now electrically operated, and seating was improved.

The last of the first-generation cars boasted further improvements to the engine, with reshaping of the apex seals to improve gas seal, improved breathing with a larger secondary inlet port and redesigned combustion recesses in the rotor flanks, and repositioning of the leading spark plug. But all RX-7s are noted for their good performance, fine handling and generous equipment levels.

At the 1978 press launch of the RX-7, Mazda president, Yoshiki Yamasaki, said — “The history of the sports car market is a study in frustration and compromise.” Happily, neither of these factors applied to the RX-7.

Kenichi Yamamoto, the man regarded as the father of the Mazda rotary, persevered with the engine originally devised by Felix Wankel, while the Germans experienced reliability issues with the NSU Ro80. When he later became Mazda’s president, Yamamoto looked back on the Wankel as an engine that captivated engineers worldwide. Although Mazda experienced its fair share of difficulties and hardships associated with the development of what was a revolutionary invention, importantly, what Mazda did was to make the rotary engine work — and, of course, it also installed it into a desirable and timeless car.