Pioneering import drag racing in New Zealand, breaking world records, and developing some of the most potent powertrains on our shores — we dive into the life of R.I.P.S Racing head honcho Robbie Ward

Robbie Ward

Age: 48

Occupation: Owner, R.I.P.S Racing

Location: Rotorua, New Zealand

Records: World’s quickest and fastest 240Z and RB30 — 7.86 seconds at 177.4mph (285.4kph) (240Z); world’s quickest and fastest RB engine — 6.99 seconds at 192.7mph (310.1kph) (FED), world’s quickest and fastest AWD and GT-R — 7.28 seconds at 194mph (312kph) (‘MGAWOT III’)

NZ Performance Car: Hi, Robbie. Readers will undoubtedly know your name for your drag racing exploits and R.I.P.S Racing workshop; can you tell us how you cut your teeth at the very beginning?

Robbie: Hi, NZPC. Leaving school, all I wanted to do was be an automotive machinist and engine reconditioner. I started doing an automotive-machining apprenticeship and became absolutely obsessed with building engines. All of my spare time after hours was spent building engines — anything I could get my hands on, just because that’s all I wanted to do.

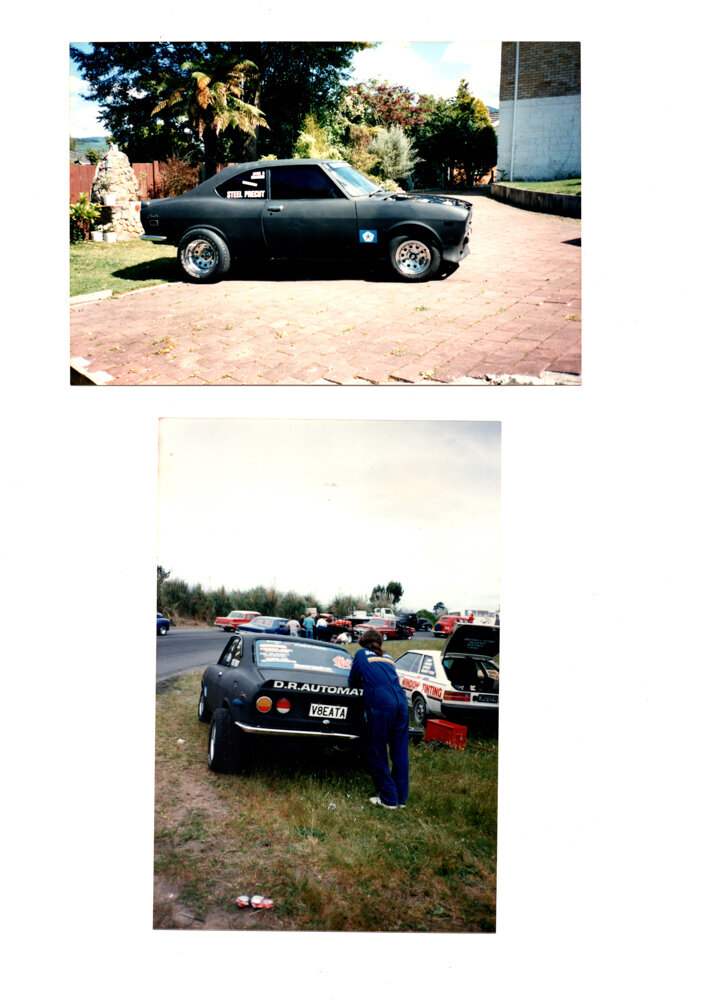

When I was about 18, I had made a lot of friends who were into cars and came across a Mazda RX-2 at a friend’s wrecking yard. Back then, they were worth nothing; I bought it for $500 or something like that. I was also into Valiants, as I had done quite a few Hemi 265 builds for customers and myself. So, in my infinite wisdom, I decided to put one into this little RX-2 coupe. That was about 30 years ago, back when everyone was an old-school bogan V8 guy. They were all absolutely laughing their asses off, telling me I was dreaming, wasting my time, it would never work, etc. That type of comment made me even more determined. As soon as people start to tell me I can’t do something or that it won’t work, as long as I genuinely believe I can make it happen, I back myself. It fuels me to prove them wrong.

Did you manage to prove them wrong with that Hemi-powered RX-2?

Oh yeah. Back in those days, there were the Ti Street drags in Rotorua. It was an eighth-mile street drag format and everyone would turn up with their Falcons, Valiants, hot rods, and whatnot. I rocked up in this RX-2 and annihilated most of them. Being a pretty cheeky little shit back then, I had rung the organizer of the meeting beforehand to ask what the rules were for the burnout comp.

He just said, “What do you mean, you f**king idiot? There are no rules — whoever makes the most smoke wins.”

So, what I did was put a tank of kerosene and diesel in the boot with windscreen washers squirting onto the tyres to make sure I’d win. That completely destroyed the whole street — sort of like the Aussie burnouts you see today. Those V8 boys were spewing; how dare this little Jappa-driving young fella come along and win. They weren’t happy about it at all.

I entered the next year with the same car, and they said, “If you want to enter the burnout comp, you can’t use the squirters.”

I thought, Sweet, I’ll make up some dual wheels out of two space savers joined together with a larger profile on the outside so that when the first pair pop it will drop down onto the second pair and I’ll just keep going. I popped all four tyres and got banned — I was never allowed back.

On the drag meet side of it, the rules had always been that the cars must be road legal with a WOF and registration, but, seeing how quick my car was getting, they brought in a pro drag car, a Vauxhall Viva with 454 that wasn’t even close to being road legal. From memory, I lost to it in the final.

That’s how I became the arch-enemy of the V8 boys; even with the Chrysler motor, the fact it was a young fella in a Japanese car with a six-cylinder at ‘their’ V8 event just wasn’t cool.

So, you were an import guy from early on; what came next?

Well, after the RX-2 I actually changed back to Valiants because of what I had been working on: the usual selection of Pacers, coupes, station wagons, and four-doors. I got quite well known for doing them; people started calling me the Hemi or Valiant man. That was right up until the R32 GTS-T started getting imported into New Zealand. The first model was an ’89, so this would have been the late ’90s, when I had a workshop at home and was repairing cars for car yards. One of the salesmen from one of the yards turned up at my place in a GTS-T and goes, “F**k, Rob, you think your Valiants are quick? Come have a ride in this.”

It was pretty quick and handled better, stopped better; it was a whole new ball game. Right then and there, I decided this was what I wanted to do, so I bought one.

With them being such new cars at the time, how did you know where to begin when it came to extracting more power?

I’m totally self-taught — from scratch. It started with a little boost tap, then playing with bolt-ons; doing the exhaust, intercooler, working my way through them. But, in that period, I never really got to finish one for myself; every time I was nearly finished one, it would get bought up — one by a Targa guy and others [by people] wanting to go fast. By that point, I had maxed out what the RB20DET could do, tried playing with a couple of RB25DEs — but they had nothing on the two-litre turbos — and moved on to the three-litres. I remember this clearly, because I made a jig for doing the tensioner relocation and it’s stamped ‘2003’. I never bought adaptors, never looked at what others were doing; just started with cardboard, drew it up, made my own adaptor plates, etc. — the old-school way.

How did R.I.P.S form out of this pursuit?

When I changed from Valiants to Skylines, everyone called them ‘Jap imports’ and I wanted to be a pro on imports. That’s how we became ‘Rotorua Import Pro Shop’ (R.I.P.S) — I used to get the odd phone call from people thinking it was a golf shop, as they call themselves ‘pro shops’ [laughs].

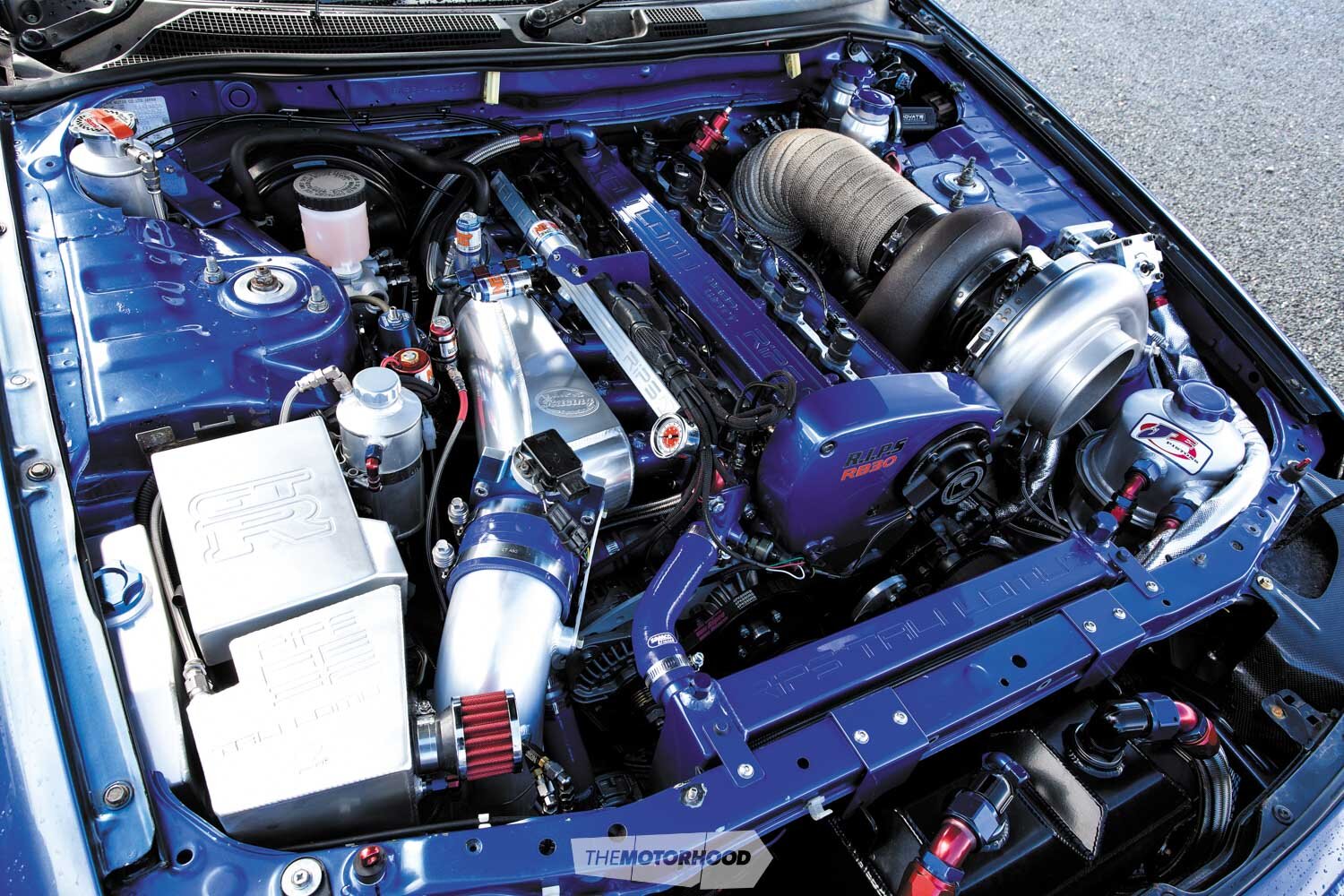

You’ve built the R.I.P.S name around the RB30; what is it about the three-litre that performs so well?

It was just far easier to make a lot of power out of them than anything else I could easily get my hands on, and it was a logical step for the cars I was working on, which were GT-Rs.

First of all, the blocks were readily available — you could get one from a VL Commodore for $200–$300 — and it had everything going for it, really. The GT-Rs already had the RB26 head, which is the best-flowing option, and that meant you didn’t need to muck around with wiring, just bolt the three-litre block straight in — it was a no-brainer. The biggest thing with them is oil control.

Second, you can’t believe everything you read on the internet; when you get told you need something to make it stronger, for example, you probably don’t need it at all.

Third is the tuning. You can have the best engine in the world, but, if you don’t have a real good tuner, you’re wasting your time — the only guy who has ever tuned engines in cars that I have built at R.I.P.S is Jason from Infomotive, and he’s done an incredible job.

People often ask what’s the most power we can make from an RB30, but, once we’ve got the car up to the kind of power we’re making, the car’s never on the dyno; we’re tuning it on the track. The most we’ve done on the dyno would have to be around 1000–1100hp [746–820kW] at all four wheels before the rolling road starts having traction issues. That’s about 90 per cent of the data we need for the final tune, and we do the rest at the track. To us, there’s no point in looking for a power figure on a piece of paper; it doesn’t mean anything. Based on the mph we ran in the GT-R, it would need to be around 1800bhp [1342kW] to achieve what we have.

At the same time, you were pushing that development back into drag racing, correct?

Yes. A doctor brought his GTS-4 to me, and he said he wanted it to go quick. I asked if he trusted me, as I wanted to do a three-litre conversion — this was before I had even developed anything. He did trust me and said to go for it. That was the original 10.2-second car; he let me use it as my guinea pig and work out how to manage an all-wheel-drive RB30 to target the GT-R market. I was very grateful for that opportunity, as, without it, who knows?

After that, the owner of the Rotorua Agrodome, Paul Bowen, dropped off his R32 GT-R and also said to go for it, so I did, and he let me run that into the low 10s as well.

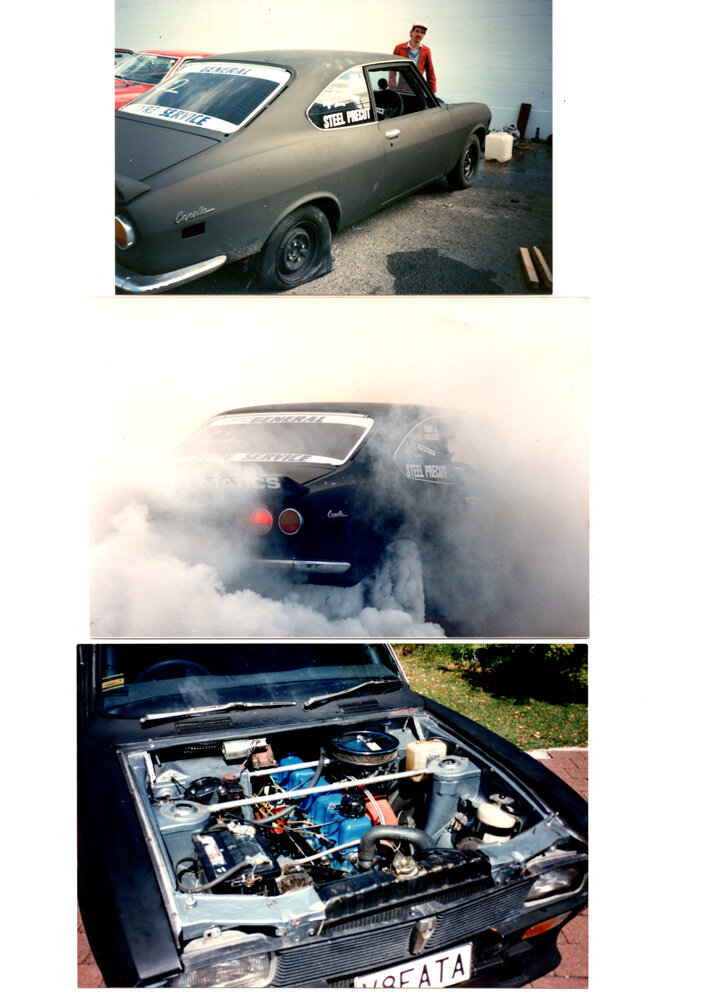

That’s when I got my first personal car since R.I.P.S started; it was the record-breaking Datsun 240Z. When I went to buy it, the guy had a small block Chev in it and had done a mid-to-low 10 — something like that — and was a pretty old-school bogan type, so I didn’t tell him what I was planning to do, as I thought he might not sell it to me. I waited until I had done the deal, paid the money, and had the car on the trailer before I told him we were going to take out the motor and put a Nissan six-cylinder in there. He said it was never going to go faster than the small block — it was just like when I was a cheeky little prick at the Ti Street drags; it was déjà vu to those Mazda days.

I ran that car into the 10s the first day out and ended up in the sevens with a world record for the fastest 240Z. It was never meant to be that quick; the idea was simply to use an already-prepared chassis to develop engines. Its sole purpose was to develop reliable, high-power engines that could be converted to four-wheel drive to use in the GT-Rs, but nothing is ever fast enough, and we kept going until we got to the point where it was getting dangerous. I knew I’d be f**ked if I crashed that thing — it wasn’t a seven-second chassis; it was a nine- or 10-second chassis. Rewatching some of the videos near the end, it was getting a bit nasty there. The final straw was when a guy from Saudi Arabia who loved the car made an offer I couldn’t refuse to buy it for his private collection.

Slightly left of field from what you had been doing, you ended up in a front-engine dragster (FED) with an RB30 after that, right?

That’s right. The sale of the 240Z gave me the money to say, “Right, what do I want now?” That’s when we found the FED. I’d never driven a dragster before, so it was jumping in the deep end with a front-engined. Everyone told me I must be pretty keen to do that, as they’re notoriously hard to drive and do real weird shit because of where you’re sitting behind the rear wheels. However, in saying that, we knew that, with that chassis, we could throw as much power as we could make at it without breaking the car. It was way safer cage-wise, and we chucked a standard blocked, standard cranked RB30 into it and ran into sixes — the world’s first RB to run a six-second pass.

That was a massive achievement in itself, despite what people thought of the FED. Was that when your four-wheel-drive system came into play?

What was starting to happen is that people expected it to be quick. The 240Z was fine, as it was a very recognizable car — people could quantify its speed; but, with a dragster, people just expect them to be quick; there’s no “Wow, that’s a fast car”, and it didn’t appeal to most people.

I had customers start saying, “You’re supposed to be racing imports; what are you doing?” They saw it as an easy way out — at least, they presumed it was easy, but it was far from it.

During the time we were running the 240Z and the FED, Reece McGregor was out there nailing his GT-R. I thought if I could ever be as fast as him, that would be the ultimate goal. But watching him, and what a few of the top cars in Aus were doing, they were all over the track; to me, every run looked like it was pretty out of control and not smooth at all, so, if I was going to beat any of these guys, who had a hell of a lot more money than I had, I needed to come up with something that meant my car wasn’t all over the track, and go faster because of it.

As soon as we ran that six, we f**ked the FED off and got back into a car, and that was the perfect timing for me to design this four-wheel-drive automatic system. Using a Powerglide, I developed it all myself. It wasn’t just a case of bolting on a bellhousing and adaptor; it wasn’t a five-minute job at all. To do it the way I did was actually very involved.

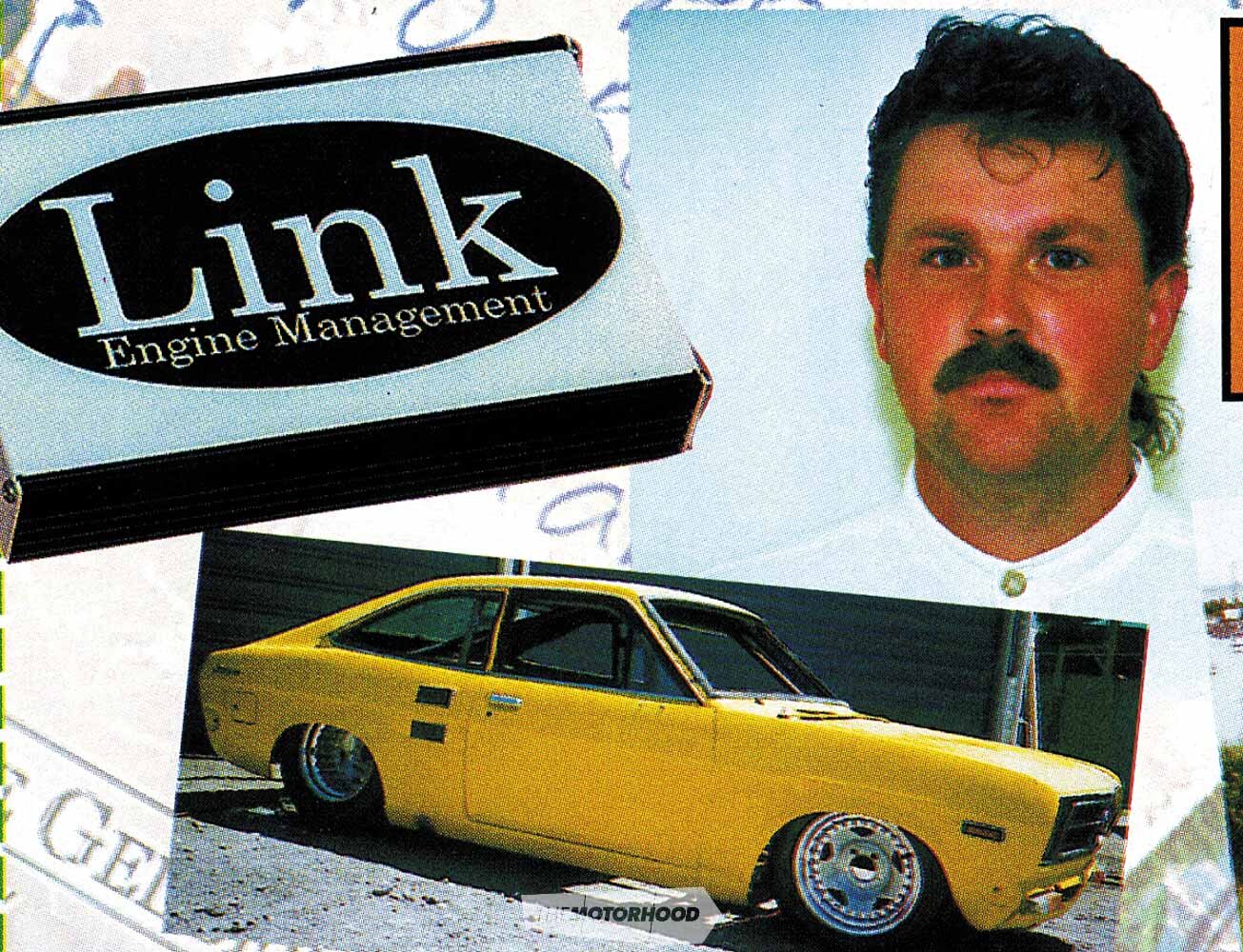

That’s what the Stagea [‘MGAWOT’] was for; I used it to develop the four-wheel drive. We needed a car to test it. A customer in England had said that if I could prove the system worked, he’d send me a whole car to build. So, I bought this shitty old Stagea and put a nice RB30 in it. Road legal, full street trim, and weighing 1800kg, it ran into the eights almost straight away. It quickly proved that the trans worked. I knew if we could achieve that in an 1800kg car, we’d hopefully be on the money putting it into a lightweight GT-R.

Is that where the ‘MGAWOT II’ and ‘MGAWOT III’ Skylines came from?

Yeah, we took everything out of the Stagea and put it into the blue GT-R [MGAWOT II] that was featured in NZPC [Issue No.] 200. Then we bought Glenn Suckling’s GT-R, which he had run for six or seven years. I believe his goal was to run a seven with a manual. Once he’d done that — and it was a massive achievement — I think he had had enough. We did a deal whereby I bought it as a roller, because it was a tidy, set-up car that was red, which most of the R.I.P.S cars have been, and suited exactly what we were trying to do. MGAWOT III was the car in which we set the record for the quickest four-wheel-drive car in the world, and also the quickest GT-R in the world, with a 7.28 at 194mph [312kph]; the auto trans was the key.

Out of all the cars that you’ve built and raced, what has been your favourite?

The 240Z was great for doing wheel-stands — there were some beautiful wheel-stands — the FED, because it was honestly terrifying; and the Stagea, because it was such an unassuming piece of shit that no one would give it a second thought; with the Stagea, I purposely entered all the V8 classes just to stick it to them. I wanted to race the best guys and the guys who were in Super Sedan, Top Street, etc. were the best drivers. The V8 classes always had the best racers, even if not the fastest cars. I wanted to be the best driver I could be, so I had to race against the best drivers. For me, it was never about being given the trophy for showing up in a tiny field of cars; you had to earn it, and if I beat the best I knew, I had earned it, which is what we did with the Stagea.

At that height of import drag racing, who did you most want to beat?

I’d always kept a real close eye on Reece. If there’s one thing about that time that I’m disappointed about, it’s that I never got to race Reece. I always wanted to have a side-by-side run, even if I got my ass handed to me. But, once I got the record, he never got it back from me, and that stood for two to three years before the Aussie boys caught up, all using autos [laughs]. My goal when I started out was to get the world record, and we managed to get it — it was a massive team effort — and not many people can say that.

Without that drag racing involvement, do you think R.I.P.S would still be what it is today? Would it exist at all?

Not even close. R.I.P.S and I are only here because of drag racing. There wouldn’t even be R.I.P.S without drag racing. Nothing else has ever been an option; it’s all I’ve ever done. That Mazda RX-2 sealed my fate.

There’s some who say that drag racing has died off in recent years; what do you reckon?

I agree that it has. Drag racing is incredibly expensive, and it requires an unbelievable amount of dedication, passion, and drive to get towards the top of any class. It’s not a hobby; it’s a 24/7, all-night, absolutely-consuming passion that will send you broke so fast it’s not even funny. I was 100-per-cent committed, and that was the only way to get to the front of the quick stuff. Most people don’t have the dedication, tuners, expertise, or money to do it. It’s not just a Sunday afternoon fun day out any more, and there’s diminishing returns. So much development is needed to get a 10th quicker or 5mph [8kph] faster; you could spend 12 months working and spend $100K to drop a 10th at the top end of your class.

The weather conditions here also play a big part. You can turn up at the track on different days and the weather is different every time. One day the track is cold; the next it’s raining; come back a week later and it’s different again. Nothing bad about the tracks themselves; it’s just the weather we get here. Ideally, you need consistent conditions to run a consistent car and slowly get on top of it, and we just don’t have that here. That’s why quite a few of the quick guys go to Aus; you can run Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday with the exact same conditions. You can get on top of your car much quicker.

More important, will we see R.I.P.S return to the strip after your crash in 2016?

What I’ll say is that the crash was far more serious than people realize. Today, nearly three years on, I’m still not fully recovered and probably never will be fully recovered. I’m not comfortable getting behind the wheel of a car at that level again and controlling it — not yet anyway.

We have thrown [around] the idea of someone else driving — I have a couple of mates who are very light and very brave, but they have no drag racing experience, and you can’t just hop in a six- or seven-second drag car and expect to make it to the other end safely. You have to build up to it. The first time you let off the trans brake in a car like this, you would probably freak out at just how brutal the acceleration is. The concern would be finding someone with suitable experience to drive, because, if I was going to do it again, it would be a five- to six-second car.

We hope to see you back out there one day, in whatever form that may take. Thanks for taking us all on a trip down memory lane, Robbie.