Ever wondered what it takes to prep and maintain an engine through a season of the Demon Energy D1NZ National Drifting Championship? Here’s what some of the teams, engine builders, and tuners have to say.

Team Jenkins Motorsport

Preparation

When the Jenkins brothers arrived at Speedtech Motorsport (STM), they were bringing in one already built RB and a completely factory SR — two very different beasts to tackle, but Chris Wall was keen to take on the challenge. Starting with Troy’s RB30, Chris stripped the already forged block and installed new bearings, piston rings, head gasket, and upgraded head studs — a simple freshen-up to maintain reliability throughout the D1 season, making use of the existing camshafts and polishing the crank. The old turbo was binned in favour of a Garrett GTX3582R with a twin-scroll Sinco manifold.

“The power and torque are definitely up there with everybody now. It’s making the same power as [the cars of] Darren Kelly and Cole Armstrong,” Chris tells NZ Performance Car. At the eleventh hour, nitrous oxide (NOS) was added to the mix, but time fell short and it wasn’t set up for the season start, so this is something that Troy is looking forward to testing in the off season for an increase to responsiveness.

As for Ben’s SR20, the team wanted to push more power out of the little two-litre without compromising reliability. “They gave me free-range over this one,” Chris says. “We were chasing quick-spool low-down torque and lots of top-end power to keep it competitive.”

The engine received an arrangement of forged pistons and rods, new camshafts and head studs, and an upgraded head gasket to prep it for the power about to be thrown at it. Everyone agreed the TD06 turbo was not cutting it — Chris says, “If you’ve got a little two-litre, it’s hard enough trying to chase down six-litre V8s” [laughs] — so it was subsequently swapped out for a new Garrett GTX3076R, which sits on top of a Sinco manifold.

Maintenance

Both engines are tuned by Chris down in Wellington at the start of a season and, thus far, have run faultlessly throughout. The team puts this down to two things: first, a list put together after each round that details things that were noted on track or found to be needing attention by the crew, and, second, the regular maintenance schedule. Both cars are put up on the hoist at the Team Jenkins shop, the engine oil is dropped to check for any contaminants then replaced with Motul 300V, and new filters are installed. The gearbox also gets a fluid change every second round with Motul Gear 75-140 to keep things fresh, while the power steering, brake, and clutch fluids are also topped up. Attention is then turned to fuel, pulling the fuel filter out and cleaning away any debris, followed by a full bolt check of the steering arms, sway bars, and mounts. One of the main issues found at this stage is the constant perishing of the boost lines — caused by the hot temperatures in the engine bay — so these are carefully checked and replaced after each round. Troy also tells us that the brothers have “been lucky enough to have Chris and the Speedtech boys at every event with us to ensure that we don’t have any problems that could hinder our performance on track”.

Engine builder/tuner: Chris Wall at Speedtech Motorsport

1989 Nissan Silvia S13 (Ben)

- Engine: Nissan SR20DET, 1998cc, four-cylinder

- Block: Forged pistons and rods

- Head: Kelford 272 camshafts, Brian Crower valves, springs, and retainers; ARP head studs, head gasket

- Turbo: Garrett GTX3076R, TiAL exhaust housing

- ECU: Link G4+ Storm

2001 Nissan Silvia S15 (Troy)

- Engine: Nissan RB30DET, 3000cc, six-cylinder

- Block: RB30E, ACL bearings, polished crank

- Head: RB26DETT

- Turbo: Garrett GTX3582R

- ECU: Link G4+ Extreme

‘Fanga Dan’ Woolhouse

Preparation

According to Zane Shelley at Checkered Flag Automotive, the key to building a reliable and fit for-purpose engine is taking the time to do your research, and this applies to any aspect of a project. Zane regularly discusses ideas with fellow crew members Glenn Sucking and Steve Murch. “We look at block options, heads, cams — everything. As you’re building, it’s like blueprinting what you’re going to do; you need to check everything,” Zane says. “It may go together two or three times before final assembly to check all the clearances and how everything is working together.” He believes that the focus should be on generating the best range of usable power in drifting instead of chasing a large dyno figure.

According to Zane Shelley at Checkered Flag Automotive, the key to building a reliable and fit-for-purpose engine is taking the time to do your research, and this applies to any aspect of a project. Zane regularly discusses ideas with fellow crew members Glenn Sucking and Steve Murch. “We look at block options, heads, cams — everything. As you’re building, it’s like blueprinting what you’re going to do; you need to check everything,” Zane says. “It may go together two or three times before final assembly to check all the clearances and how everything is working together.” He believes that the focus should be on generating the best range of usable power in drifting instead of chasing a large dyno figure.

The current LS3-based engine has been developed as the team dialled in what Fanga likes over four seasons and was also directed by the need to reduce the number of clutch kicks that “destroy shit”. The previous set-up had already destroyed three 14mm high-tensile bolts in the driveshaft, which Zane tells us is “almost unheard of”, which raised concerns over the amount of grip the chassis had and forced the team to reduce the grip to accommodate the power range.

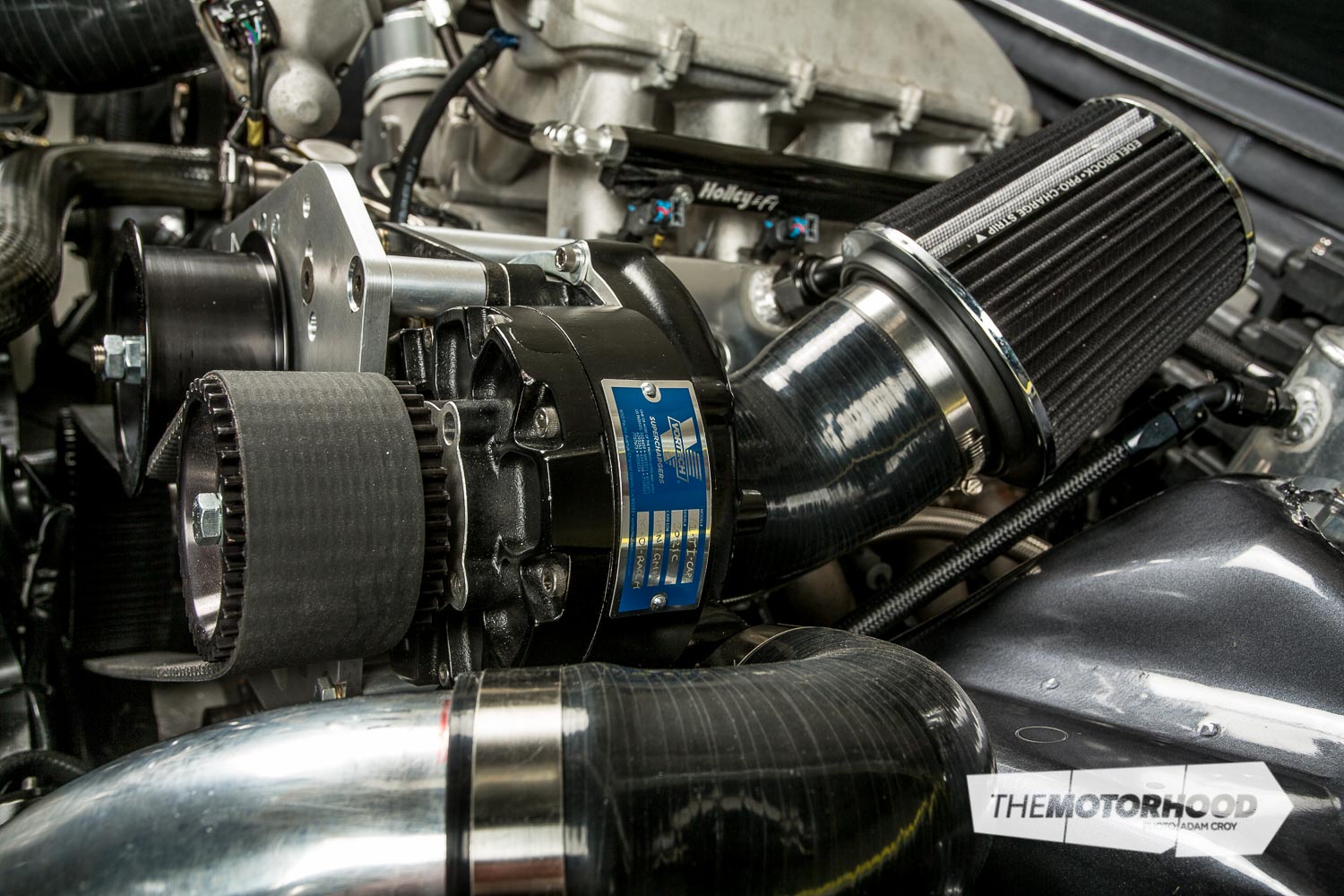

That it was already making 410kW at the wheels naturally aspirated only highlights the amount of grip that’s built into the VE chassis. This was when the supercharger came out to play, with Fanga wanting more torque and horsepower: “It was Dan’s idea to supercharge it — he felt [that] the turbos muffled the deep V8 rumble and [he] wanted to keep that alive. It actually made it a lot easier, too, as we didn’t have to muck around building exhaust manifolds and other bits.”

And the result? “We’re more than happy [laughs]. Shit, we were making 410kW at the wheels already, and, on our first dyno session, we pulled the pin after making over the power figure we were chasing at six grand [rpm]. The car normally revs out to seven and a half grand [rpm],” says Zane.

The team knew it was at the limit of the gearbox, so the decision was made to pull back the boost to a reliable eight pounds, making an impressive 633kW (850hp) at the wheels. “Dan is smart enough to know that a season is more than just the dyno sheet. It doesn’t have to wring its neck out to make power anymore and will be a lot more comfortable to drive,” Zane says. Seven hundred revs per minute were pulled out of the rev limiter in tuning due to the engine reaching upwards of 8000rpm on some tracks — Nascar engine, this is not; it is still running a standard steel crank out of a Holden LS.

Maintenance

Zane adheres to a strict maintenance schedule to preserve the optimal performance of the VE’s powerhouse. “We do a camshaft and sprocket [cam-gear] replacement at the start of each season,” Zane tells us, “and repeat this halfway through the season to prevent wear and tear that could cause further damage if the part were to fail.” This is alongside opening the heads to replace the valve springs at season start and to check the valve clearances every two meetings, as the package runs solid rollers, which can alter the positioning.

After the practice sessions at each meeting, Fanga completes an oil change to run fresh oil for qualifying battles. At the same time, the oil filter is split in half to check for foreign materials. If anything is amiss, the team pulls the pin before qualifying for a more rigorous check-over so that the safety of the engine can be preserved.

This process saved the team during the Taupo round of the 2012/’13 season, after discovering a cracked oil pump during the oil change. Zane drove down from Whangarei, arriving in Taupo at 6pm that night to strip the engine back and complete a rebuild. The car was loaded onto a trailer at 6am the following morning to head off for the battles. Fanga went on to win the round (and, later, the season championship) — although Zane wasn’t overly happy about the four-minute-long celebratory burnout on 40 pounds of oil pressure …

2010 Holden Commodore (VE)

- Engine: GM LS3, 6000cc, eight-cylinder

- Block: Factory aluminium LS block, forged Wiseco dome pistons (13.4:1 compression), Eagle H-beam rods, 25-per-cent underdriven crank pulley, factory stroke crank, Comp Cams CNC oil pump, Comp Cams double-row timing chain

- Heads: Flowed heads, stainless one-piece race-series valves, multilayer steel (MLS) head gaskets, ARP main and head studs, Comp Cams custom solid lifters and valve train

- Supercharger: Vortech V-1 Ti-Trim

- ECU: Link G4+

- Engine builder: Zane Shelley at Checkered Flag Automotive

Daynom Templeman

Preparation

A testament to what a strong well-built engine can achieve, the current 2JZ-GTE VVT-i package originally lived inside Daynom’s FD RX-7 ‘Ginger’ and was later moved to the current E46 BMW chassis. The engine was the culmination of the team’s trip to Singapore four years ago, when the FD was still running a 20B rotary. “We got smoked; we really got our pants pulled down,” Ross tells us, “that’s how far we were behind in terms of power and reliability.”

Already having built a series of high-power, successful 2JZ packages, it was a no-brainer when deciding on what powerhouse to swap into the car, and it was something they didn’t need to reinvent the wheel with to achieve reliable power figures. Taking notes from Daigo Saito, the team built a similar combination but went one step further with each component. “We overbuilt the engine for reliability, with bigger injectors, fuel pump, lines, manifold, and upgraded the ignition. Everything had to be the most efficient,” he says. Turbo man Steve Murch was tasked with putting together one hell of an air blower, which came in the form of an MSE-specification Holset hybrid.

With the way the rules were going locally in the Demon Energy D1NZ series, and the fact they were catching up to those overseas with the inclusion of NOS, it was an easy decision to make to squeeze out that extra bit of torque by installing a nitrous system. But, Ross says, “It’s almost uncontrollable; we very rarely run it. It’s making 1200hp as it is, without running the NOS.”

Maintenance

After every meeting, the team completes a valve-spring and clearance check to ensure nothing has gone amiss in the head — that is, a dreaded dropped valve — and a spark-plug check, compression test, and leak-down test are always undertaken for basic maintenance and issue detection. The tappets are reset after every third meeting, while Ross maintains the Link G4+ Fury ECU. Plugging in and downloading the data allows him to check over the oil and fuel pressures, ethanol content, what’s happened on the knock, and if there are any issues with fuel or oil surge.

Ross admits that it’s “a matter of keeping on the ball at all times. That’s no different to any type of racing; drag racing, rally, jet sprinting — any sort of motorsport, you need to have that maintenance schedule down tight. That’s something we really stress to our customers.” Ross has worked with some of the most familiar faces of the D1NZ series, including Chad McKenzie, who, at the time of writing, has already won the Pro-Sport class with no engine issues, which he puts down to keeping to the regular maintenance schedule set out by Ross.

Curt Whittaker is another name on Ross’s list of D1NZ drivers he has worked with. Curt used to have three RB engines for his Cefiro that would be rotated between the car and the shop. After every meeting, the engine would be pulled out and dropped off for a full strip down while one of the already prepared spares would be put back in the car — in the case of Daynom’s car, with its 2JZ set-up, this might be a little redundant, but it would never hurt to have a spare!

The E46 was initially tuned on 98-octane pump gas until Christmas last year, when the switch was made to E85 with a flex tune. The flex sensor measures how much ethanol is in the system and can calculate running figures to compensate for the difference rather than shutting down. At a practice meeting, this feature was accidentally put through its paces when another team’s 98-octane fuel was put into Daynom’s car. Daynom came in and said “Hey, we’re down on power, can you check it out?”, which is when a simple plug into the ECU was able to tell Ross that the ethanol content was down to 40 percent, and the Link G4+ Fury was adjusted.

Tuner / Engine builder: Ross Honnor at Dobsons Dyno Tune

2001 BMW 330i

- Engine: Toyota 2JZ-GTE VVT-i, 3400cc, six-cylinder

- Block: Engine Specialties machined block, Carrillo 8.5:1 pistons, Carrillo rods, BC crank, ACL bearings, ARP studs, deleted oil squirters, Accusump, swinging pickup, pivot-drive oil pump

- Head: VVT-i head, Engine Specialties porting, BC cams, Ferro valves, Daynom Drift–spec valve springs, Daynom Drift–spec buckets

- Turbo: MSE-built Holset

- ECU: Link G4+ Fury

This article originally featured in the June 2016 issue of NZ Performance Car (Issue 234). You can grab a print copy or a digital copy of the magazine below: